As a UK General Election is budding, PM Sunak announced that he had asked the King to dissolve Parliament, with an election to be held on 4th July 2024.

The likely winner will be the Labour Party, led by Sir Keir Starmer. The opinions have been heavily weighted towards Labour for many months, in response to the perceived failings of the Conservative Party in recent years.

Dissolving Parliament is one of the Sovereign’s Royal Prerogatives. These are ancient powers that are part of the monarch’s authority, though in modern times the sovereign executes them on the advice of his ministers, namely the PM and the Cabinet. Other prerogatives include control of the armed forces, appointing and dismissing ministers, declaring war, granting Royal Assent to parliamentary bills, etc.

What, though, is the historical process of this act? And how did it emerge?

Magna Carta, de Montfort and King Edward I Longshanks

King John, who ruled from 1199-1216 AD, is noted to this day amongst the worst English kings. Whilst he wasn’t as absent from the kingdom as his brother and predecessor, Richard the Lionheart, John’s reign was typified by excessive taxation, potential sexual harassment and assault of his noble’s wives, and state corruption in his person.

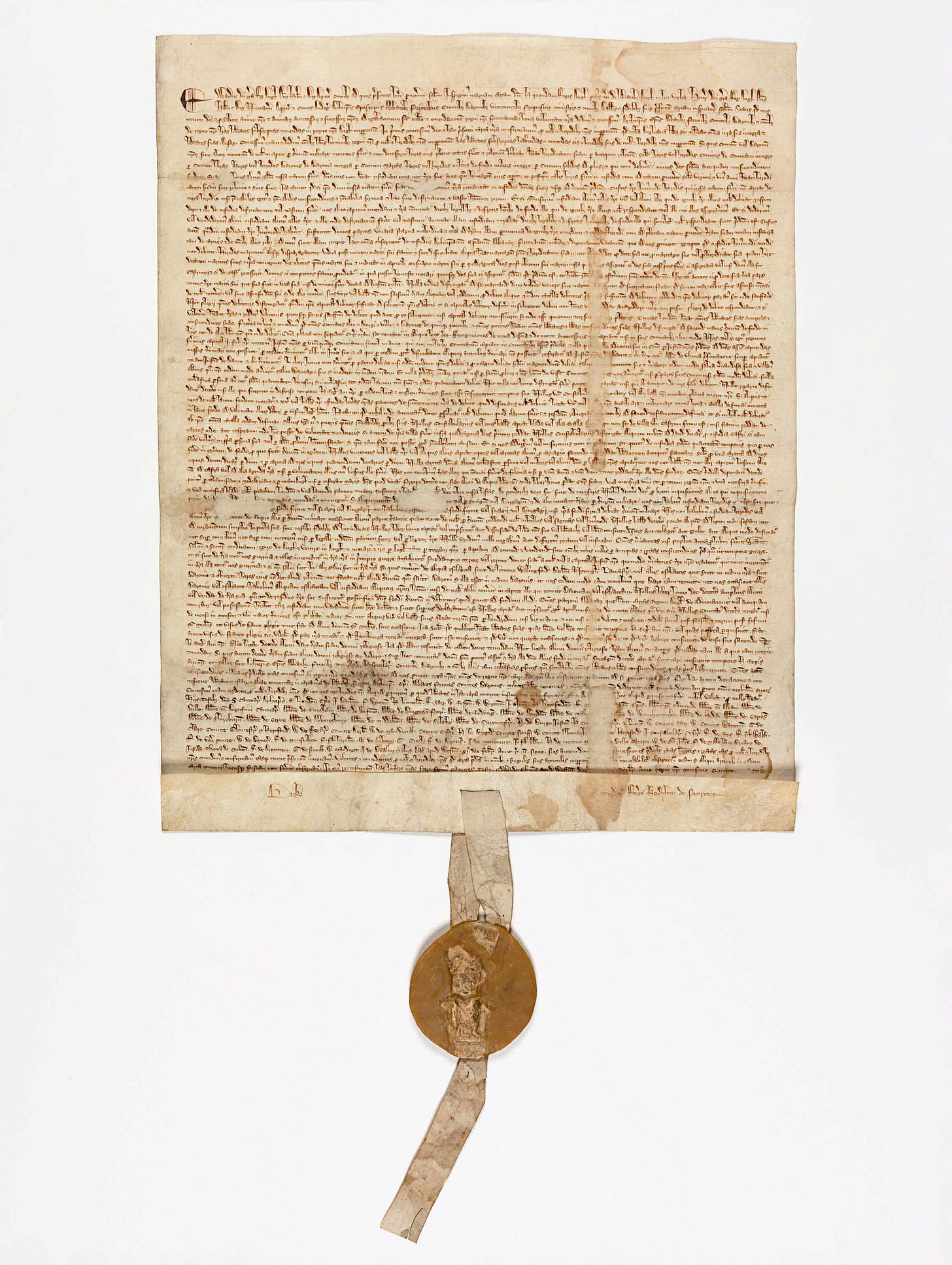

His barons rebelled, leading to the First Barons’ War, and the signing of the Magna Carta (or Great Charter in English) as a peace treaty. Whilst we view the Magna Carta today as the beginning of modern civil liberties, it was then seen as a remonstrance by the nobles and a general statement of grievances against the king. John died in 1216 AD, leaving his young son Henry to succeed him. The barons, as a central part of the feudal system in providing arms to the king in times of war, felt excluded from the legislative framework. A principal clause in the Magna Carta was a regular assembly to aid in the realm’s good governance. It was from this clause that the first Parliaments were assembled and gained their legitimacy.

Magna Carta was re-issued very early in Henry’s reign, to reinforce the peace gained under his father’s reign. However, over time, Henry III’s rule proved in some ways as strained as John’s.

Henry III was seen to have had royal favourites, leading to mismanagement of the state. As Henry reached middle age, he like his father faced a civil war, in the Second Barons’ War led by Simon de Montfort.

de Montfort was the Earl of Leicester and led a rebellion in response to Henry’s negative rule. For a time, he managed to subdue Henry and take control of the state. Henry ruled in name, but the affairs of the state were run by de Montfort. To further reinforce his rule, he called a Parliament of the shires, where nobles, senior clergy, and representatives from towns and communities met to discuss the affairs of state. de Montfort knew that he had to consolidate his rule and gain allegiance especially as Prince Edward - Henry III’s son and heir - was still alive albeit as a prisoner of the new regime. Of course, Prince Edward would later be known as King Edward I Longshanks, succeeding his father as king in 1272 AD following Henry’s death.

It was the then Prince Edward who was instrumental in defeating de Montfort at Evesham. After escaping captivity, he assembled an army under his father’s blessing, and defeated the rebels decisively. de Montfort’s corpse was heavily mutilated at the battle scene following his death, perhaps as both punishment and warning to those who would opt to challenge royal authority.

Following participating in the 8th Crusade in the Levant, Edward became king and commenced his conquest of Wales and subjugation of Scotland. In 1295 AD, Longshanks reissued the Magna Carta in conjunction with the hosting of the Model Parliament. This was based on the body de Montfort called, which on the surface may seem odd as he was his enemy at the time of the Barons’ War. However, he possibly came to realise that consensus was required to govern effectively and that he had learned from the errors of his father and grandfather (King John).

Prerogatives

King Edward’s Parliament is called the Model Parliament as it served as a template for future assemblies. Those of his son and successor, Edward II, followed the same format. As did those of Edward III, who utilised the system to gain national buy-in for the Hundred Years War.

As Magna Carta was signed by a king, it was thus the duty of all sovereigns to adhere it to and ensure its terms were administered.

To this end, Longshanks called on all nobles, bishops, and leading town merchant representatives to assemble, and discuss key issues of state. The summoning of Parliament thus became a key prerogative of the sovereign - exclusive to him alone to call or dismiss as he wished.

Moreover, the monarch dictated the legislative agenda. He would call Parliament to suit which need he had of monies, or laws that were urgent to pass. He could pass laws whenever he chose, via edicts or writs, for instance. He also didn’t need Parliament to declare war or appoint anybody to serve in his government as a minister.

However, he had the periodic right to call Parliament, which was done several times by King Edward I, and with all subsequent monarchs until the Bill of Rights in 1689 AD. From that point, due in massive part to the trials and wars of the 17th century, Parliament became sovereign and could make or unmake any law it chose. With the evolution of Cabinet government led by a Prime Minister in the 18th century, the contemporary British constitution started to emerge.

So we can note that as a king commenced Parliament as an institution, the sole right and capacity to call and dissolve Parliaments rests with monarchical authority.

The modern format

As of the British constitution in 2024 AD, the PM advises the King of a wish to dissolve Parliament. As with all other Royal Prerogtives, this is often realised, even though it is a power legally vested in the Sovereign who in this case acts on the PM’s advice.

This is evidently a far cry from the practice from the late 13th to the late 17th centuries.

So how did the modern practice emerge?

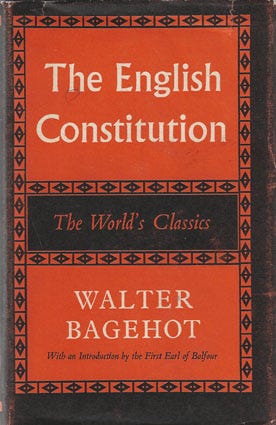

By the 19th century, the PM and Cabinet had emerged as the main executive body in the state. Whilst the monarch was the formal source of executive, legislative, and judicial powers, it had become evident that the PM and Cabinet exercised far more active executive roles, and acted on behalf and in the name of the Sovereign. This was reinforced by Walter Bagehot in his seminal work “The English Constitution” - where he mentioned the “dignified” and “efficient” arms of the state. Queen Victoria, as the sovereign at his time of writing, represented the dignified facet, whilst the PM, Cabinet and all other ministers formed the efficient function.

The expansion of the franchise via the Great Reform Act also contributed to the rise in Cabinet government, as politicians had a wider base of whom to gain the favour of. Prior to that, the House of Commons was dominated by the gentry and voted for by landowners of a specific financial endowment. In short, only wealthy men could vote. Working-class men couldn’t, and women were excluded from such.

It is very likely that PM Sunak’s Conservative predecessors and forebears such as Disraeli, Lord Derby, and Sir Robert Peel in kind advised the monarch on the dissolution of Parliament.